Some fracture areas that were formed during the Carboniferous and the Permian had continued to evolve and Pangea started to fragment, initiating the Alpine cycle.

During the Triassic, the topographically lowest areas of the future Iberian Plate were occupied by extensive alluvial plains that were periodically invaded by the sea and they were converted into shallow marine platforms; carbonate mud was deposited in these and some reefs emerged. Towards the end of the Triassic, 50 million years after the start of the Pangea fragmentation, those initial fractures had evolved to form some large fault systems that delimited depressions similar to the present day African Rift valley. One of the “rift” valleys is located in the future Pyrenean area and the other, more important and which was immediately invaded by the sea, in the area occupied by the actual Betic Mountain Range, the Alboran Sea and the Gibraltar Strait. Other similar depressions were opened in the interior of the Iberian Plate. These fault systems favour the ascension of basic volcanic and sub-volcanic rock masses.

At that moment, in the future Iberian Peninsula two emerged massifs stood out: the Iberian Massif (the future Meseta, Plateau) and the Ebro Massif, today disappeared, which occupied the present eastern areas of the Ebro Basin, of the southern slope of the Pyrenees and of the Gulf of Lion. Geographically, both massifs were islands surrounded by vast flooded areas in which salts, gypsums, clays and carbonates were deposited in some very arid climatic conditions. Between the Iberian Massif and the boundary of the Triassic swamps an extensive dessert-like plain was opened.

With the passing of time, during the Triassic and especially during the Jurassic, the extension along some of the faults that limit the rift valleys progressed until generating oceanic crust, and in this way new tectonic plates were individualized. The opening of the central Atlantic had started (figure 6).

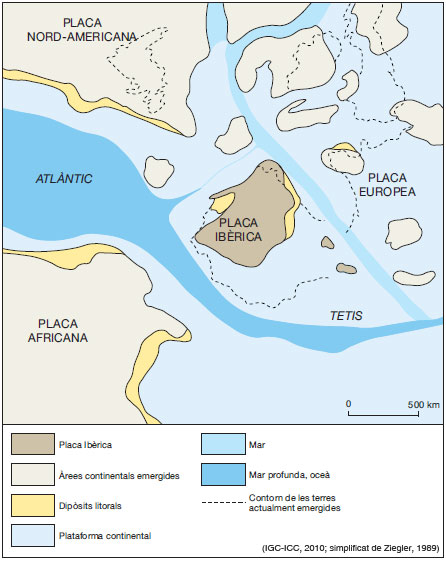

Throughout the Jurassic, during a period of 55 million years, an important part of the future Iberian Plate remained submerged in a shallow sea (figure 7). In climatic conditions that were warmer than the present ones, mud and carbonate sands were deposited on the broad continental platforms, which to a greater or lesser degree, were later shaped by the seas. Those environmental conditions also helped the waters to be colonized by very numerous groups of cephalopods, mainly ammonites and belemnites, and also by brachiopods and bivalves.

Towards the end of the Jurassic, some 150 Ma ago, the southern coasts of the Iberian Massif had separated around 500 km from the northern coasts of Africa. Throughout that period, the Tethys Ocean had already connected with the young Atlantic, which at that time had reached a width of 1 000 km, between the southern coasts of Newfoundland and the western coasts of the Sahara (figure 7). The rift valley which had started to open in the actual Pyrenean area 50 million years ago was now a very deep marine trough connected to the broad continental platform which occupied the eastern half of the present Iberian Peninsula.

Contact

Contact